A-U major-groove base triples flanked by A-minor base triples ( Figure 2) ( 8, 9).To stabilize RNA, the ENE folds into a stem-loop structure containing a U-rich internal loop, which sequesters the downstream 3′-poly(A) tail or a genomically encoded A-rich tract into a triple helix (ENE+A) composed of mostly U Recently, a unique RNA stability element known as an ENE (expression and nuclear retention element) was discovered near the 3′ end of viral and host long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), as well as in viral genomic RNAs ( Table 1) ( 4, 6, 7). All plasmids have been described in detail previously ( 2, 4, 6, 7). Downstream of class II ENEs are a genomically encoded A-rich tract (purple box) and a tRNA-like sequence (orange box). All ENEs (green boxes) are inserted into the ApaI site in the 3′-UTR. Lengths (in nts) of introns and exons are given below. Introns are represented by black lines, exons are represented by boxes, PTC denotes the premature termination codon, and the RNase P cleavage site is denoted by an arrowhead. There is a FLAG tag (not shown) at the N-terminus of the β-globin sequence.

Each β-globin sequence is flanked by a human CMV immediate-early promoter at the 5′ end and a bovine growth hormone polyadenylation (BGH pA) signal at the 3′ end. In contrast, RNA stability elements are typically studied in the context of an intronless β-globin reporter ( Figure 1, βΔ1,2), which accumulates to much lower levels than its intron-containing counterpart and exhibits predominantly nuclear localization ( 4, 5).įor all constructs, the backbone vector is pcDNA3 it also contains neomycin resistance and ampicillin resistance genes (not shown). Destabilizing RNA elements are typically studied in the context of a wild-type (WT), intron-containing β-globin reporter ( Figure 1, β-WT), which generates a highly stable transcript that localizes predominantly to the cytoplasm ( 3, 4). The β-globin reporter system has also been used to study RNA elements that stabilize or destabilize mRNA. These mutations create a premature termination codon (PTC) that renders the resulting β-globin mRNA susceptible, or sometimes resistant for rare mutations, to nonsense-mediated decay ( Figure 1, β-PTC) ( 1, 2). Historically, reporter plasmids encoding the human β-globin gene were instrumental in understanding nonsense-mediated mRNA decay because the β-globin gene from β-thalassemia patients contains naturally occurring nonsense mutations. The β-globin reporter system has been adapted to study various facets of messenger RNA (mRNA) processing, particularly mRNA decay in eukaryotic cells. This methodology can be applied for the study of any nuclear RNA stability element using the intronless β-globin reporter. This entails the transient transfection of mammalian cells with β-globin reporter plasmids, isolation of total cellular RNA, and detection of reporter mRNA via Northern blot.

Then, we provide a detailed protocol for quantitative measurements of steady-state levels of β-globin mRNA.

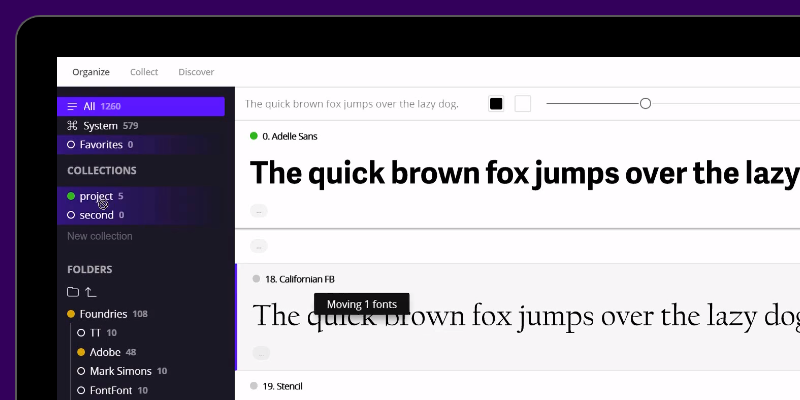

#FONTBASE WITHOUT A VIRUS HOW TO#

In this chapter, we provide a brief description of how to insert an ENE sequence into the 3′-untranslated region of an intronless β-globin reporter plasmid using basic cloning technology.

A list of considerations is included for the use of ENEs as a tool to stabilize other RNAs. In this chapter, we explain how to perform the β-globin reporter assay using the ENE, a triple-helix-forming RNA stability element that protects reporter mRNA from 3′-5′ decay. Insertion of a stability element leads to the accumulation of intronless β-globin mRNA that can be visualized by conventional Northern blot analyses. The intronless β-globin reporter, whose mRNA is intrinsically unstable due to the lack of introns, is a useful tool to study RNA stability elements in a heterologous transcript.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)